I recently came into the possession of a brand new mouthguard. My first mouth guard if I’m being honest. The result of clenching my jaw so hard that I wake up with lockjaw and a migraine if we’re telling *secrets*.

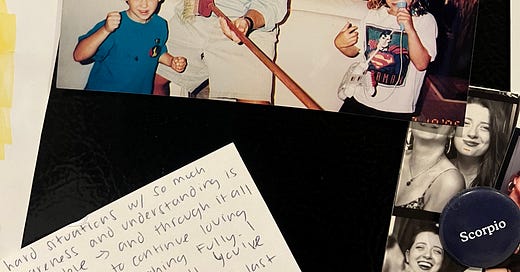

When I asked The Claw ( a group of women I’ve known since I was 6, no further explanation needed here) if anyone else has had a mouthguard, almost every single one of them responded with a version of “Yes, of course. Life is stressful and our mouths are fucked, how has it taken you this long to get one?”. I felt a little behind on the “we’re all going to the dentist regularly because we’re good at being adults” memo. But I guess these things we’ve collected as adults seem somewhat assumed and don’t always feel necessary to share—mouth guards, wrinkles, attachment styles, stress, debt, small joys, new hobbies, tax deduction loopholes, moles.

My body began revolting soon after my dad got sick. I thought I was managing relatively well, but the body doesn’t lie. My brain said, “Business as usual,” but my body said, “You got GOT bitch”. I am currently the proud owner of a rash that has been dormant in my system since birth but now blooms red around my eyes when anxiety spikes, hemorrhoids that I convinced myself were stage four colorectal cancer (a tale as old as time), and an underlying but everpresent fear that someone will break into my room and kill me. What, do you not sleep with a knife on your bedside table? Oh, you’ve never moved your dresser in front of your door because your dog growled in the middle of the night? Ok, what’s it like to be God’s favorite?

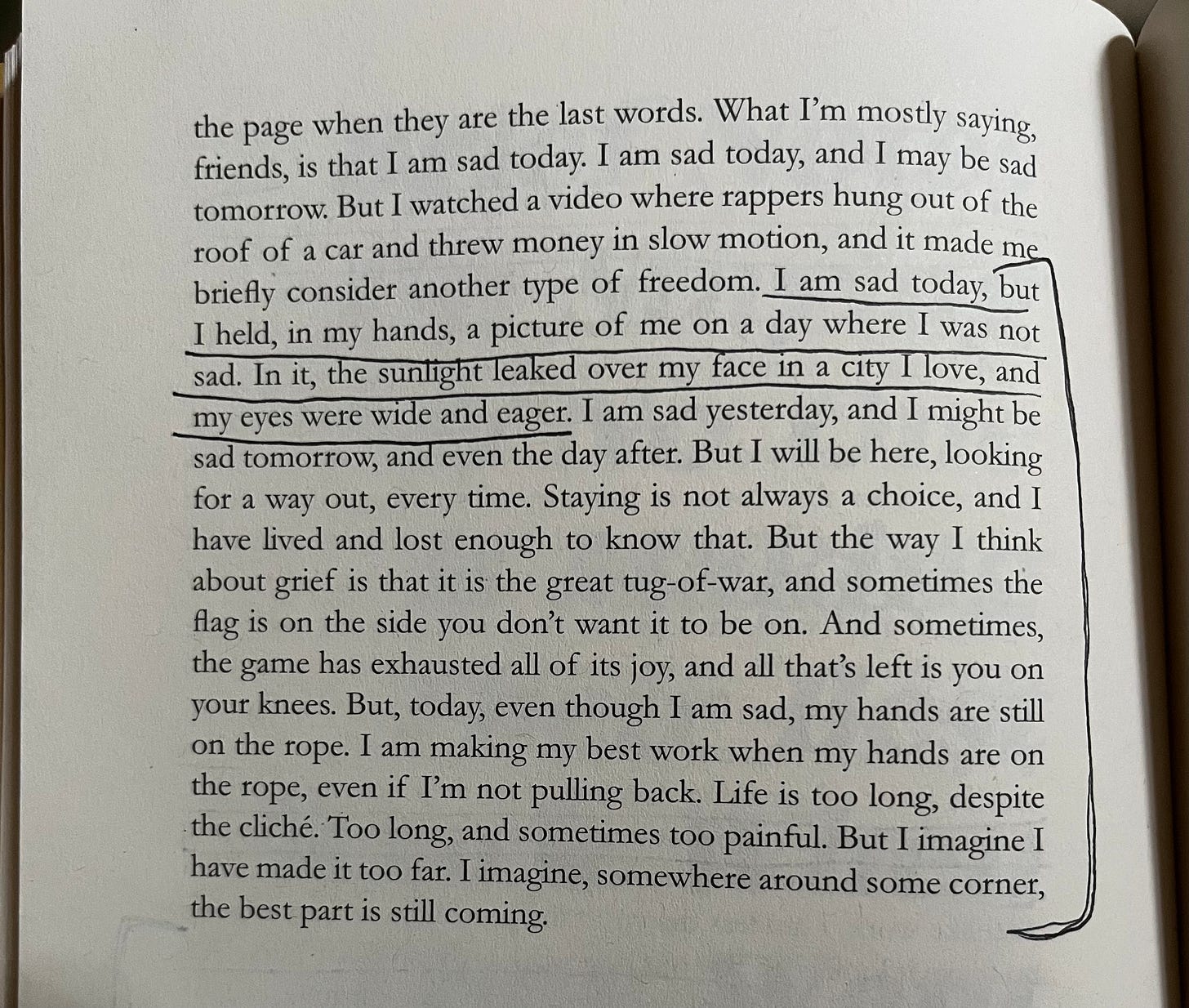

Anticipatory grief is fun in the sense that it is almost always also ambiguous. Loving someone with a degenerative disease means losing them over time and making peace with the different ways to say goodbye. Life always continues, and so does grief in its many forms. It blooms alongside the seeds you haphazardly scatter in your garden. It lingers in the background when you re-download and delete dating apps, and it watches from afar when you tell someone that you love them. It lives in your friendships, the new ones, the old ones, and the ones that fade away. It partners itself with good news as well as universal loss. It joins you while you shop for tomatoes, take your dog for a walk, and brush (or forget to brush) your teeth. Grief itself doesn’t make us special, but it does signal to us that we are still alive. And saying goodbye over and over again also means saying I love you.

Pssst: If you need to feel like your own individual grief is sometimes special, then I’m happy to be the one to tell you that today, it is. I need to feel like mine is special sometimes. And if you need to feel like your grief is small in comparison, then I’m here to tell you it’s small enough to hold in your hand and that you’re holding it well. Sometimes, I need to feel like my grief is a penny to slide into my shoe. Your grief, your rules. Not aiming for perfection here.

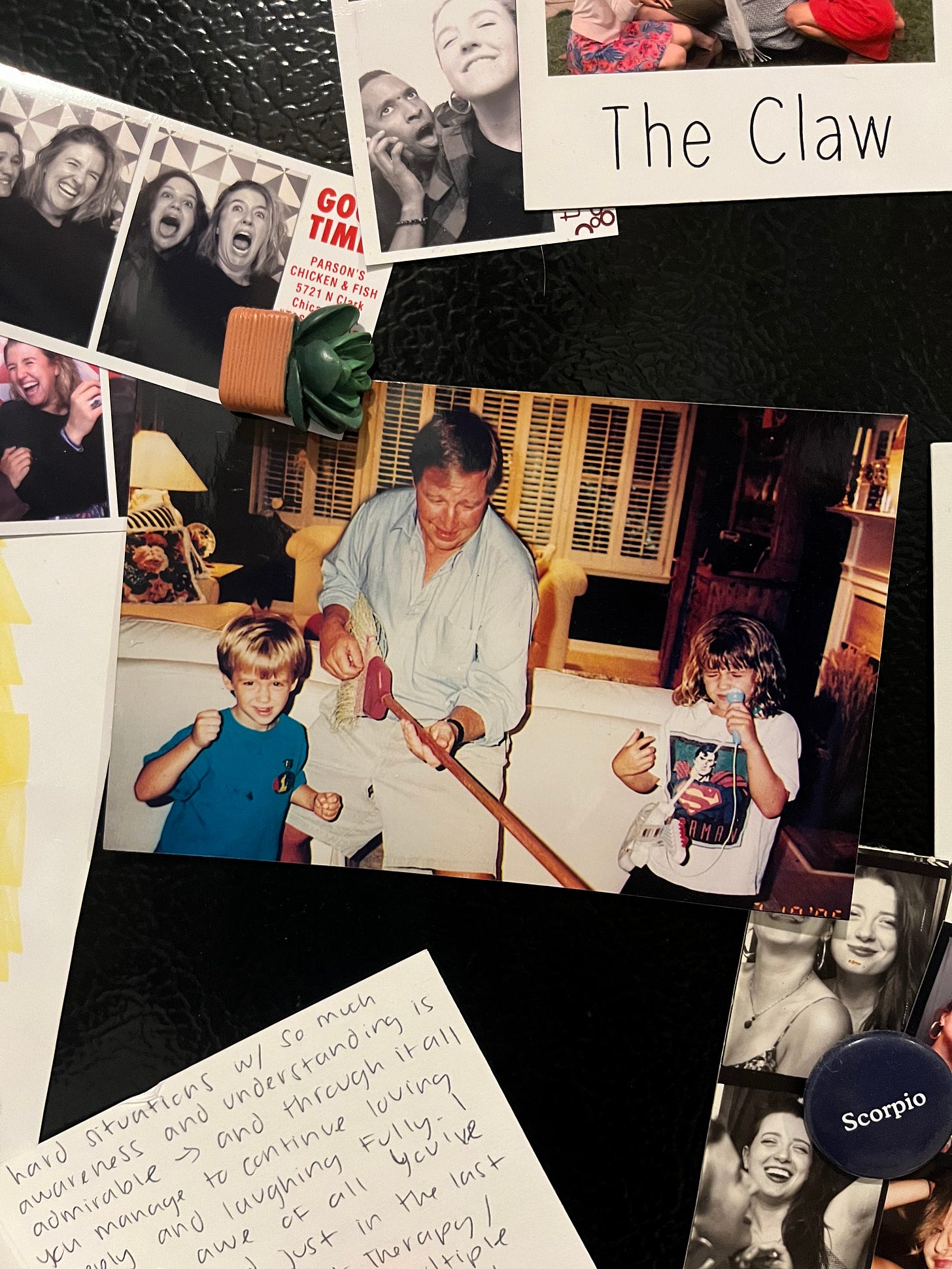

Last Spring my dad and I were sitting at the dinner table while my older brother Josh walked the dog. Dishes were still out, a bowl of hollowed-out clams sitting lopsided in the center of the table. We were full of pasta and a long day. My dad was lost in thought, and I watched him, wondering where he was placing himself in his mind. His head tilted, and his hand was on the table, one finger tapping slowly. I felt as if he were in a memory, but he could have been wondering which episode of Yellowstone he wanted to tell me about again or concentrating on the parsley stuck in his front left tooth.

He lingered in a pregnant pause I’ve known for my entire life, one that my siblings and I spent the majority of our childhood rolling our eyes at. Stories that would take the rest of us 5 or 10 minutes to tell stretched into the 45-minute range if my dad was at the helm. Sometimes a pause would be long enough for another story to start, which it would, and then he’d launch back into his, a little irritated that someone else had the nerve to interrupt a story we all had assumed was over.

His finger continued to tap, and then suddenly, as if waking from a nap, he came back to himself. He looked at me and smiled a small smile. I continued to look at him, studying his face.

It was now my dad’s turn to look at me and wait for me to talk, but I was lost, looking beyond his face for the versions of him who took me to soccer practice and interrupted slumber parties with bad jokes.

“What?” he asked.

“I just love ya, Dad.”

“Ohhh” he said, pouting his lip and starting to choke up. My dad is comically quick to cry. “Well I love you too”.

I wanted to say more. The moment felt important. Like a story I’d tell myself as comfort later once this was over and in the past. A version of myself who got to tell her dad exactly how she felt in a succinct and clean way. But I am my father's daughter, quick to cry and earnest in an embarrassing way. I stumbled into telling a long and messy version of I Love You, and he spent the next 30 minutes telling me a story about his father. Later, after Josh and I helped him into bed, I washed the dishes in a silence that felt like a hug.

I wasn’t sure how to spend this Father’s Day, maybe and most likely the last one I’ll have with my dad still alive. It was a relatively quiet day. The day before was spent on the phone with family trying to reach my dad, who has become increasingly more unreachable since he’s been admitted to a memory care unit. I got myself out of the house in the afternoon to meet some friends. I spent the night checking my phone for news but also laughing and eating pizza with people I’m so lucky to love. My grief sat at the table, but so did my friends, and in a way, so did my dad. It was a night he would have loved, a table of good conversation is his favorite place to be. He’d prefer a rack of ribs and a family-style serving size of cole slaw (mayo based, duh), but he’d still enjoy the pizza, taking time to remark to the host that “he wasn’t fucking around” and that the dipping ranch was “seriously good”.

Sunday morning, I finally got him on the phone and told him Happy Father’s Day. Our conversation was brief but sweet. My siblings and I shared photos of Dad in our group text, most of them funny: my dad shooting finger guns at the dinner table, my dad shooting finger guns at my sister’s rehearsal dinner, and my dad shooting finger guns at my high school graduation. I know that they felt the same way that I did, exhausted by the waiting and simultaneously grateful for the time.

I took myself on a bike ride to get out of the house. I rode down Kedzie to Bryn Mawr to the North Branch Trail, passing dads pushing strollers and long lines for brunch. The trails were relatively empty, and I could go as fast as I wanted, which, to be clear, is 12 MPH. I thought of my dad often, but I also thought of the trash I should take out, an essay I needed to finish, and what I wanted to make for dinner.

This process has taught me so many things, but one of the most sobering yet, at times, comforting is that you can’t control how people leave you. This is the end half of my dad's life, the hardest part of his illness, no matter how much I wish it weren’t. We’re here, and it’s happening, but so is everything else, the same way everything else happened leading up to now and continues to happen. I am not special, but I am alive, and there is still time to say I love you.

I love you, I love you, I love you.

This is beautiful, thank you for sharing 🩷🩷🩷

So beautiful Layne ❤️❤️